FAME: study days report

- Record

In het voorjaar van 2022 organiseerden we drie studiedagen rond het gebruik van gezichtsherkenningstechnologie in de cultureelerfgoedsector. De drie centrale thema's waren de juridische en ethische aspecten, de uitdagingen bij opschaling en de impact op collectieregistratie. Lees het verslag van de studiedagen hier.

Meemoo will complete its ‘FAME (FAce MEtadata): registration practice for metadata-driven facial recognition operationalisation’ project in September 2022. FAME is a network project funded by the Flemish Government which we’re running in 2021-2022 in collaboration with Ghent University’s IDLab as our technical partner and ADVN (Archive for National Movements), the Flemish Parliament Archives, KOERS Museum of Cycle Racing and Kunstenpunt (Flanders Arts Institute) as content partners.

The (international) cultural heritage sector has seen various projects on the application of Artificial Intelligence (AI) and Machine Learning (ML) over recent years, predominantly looking at facial detection and recognition to find and describe content in collections.

These projects will continue to move forwards, but they raise a lot of questions, such as: Why is facial detection and recognition important for the cultural heritage sector? What can we learn from FAME and other projects? And what challenges do we need to consider as we continue to roll out facial detection and recognition? In order to answer these questions, we organised three study days in the spring of 2022, each focusing on one aspect of the application of facial recognition technology in the cultural heritage sector:

Legal and ethical aspects

Challenges for scaling up

Impact on collection registration

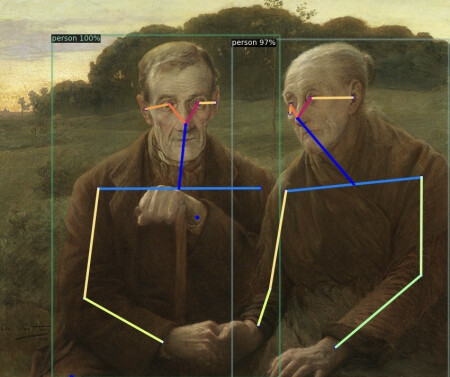

Image : facial detection applied to ‘Het bestuur van het Brugse smedenambacht’ by Bernardus Fricx, Musea Brugge, photo Dominique Provost, public domain

Main findings from the study days

1. Legal and ethical challenges

We encountered legal and ethical as well as technical challenges in the FAME project. Finding an answer to these issues is both useful and necessary for the scaling up that meemoo has in mind, and for other organisations in the cultural heritage sector who want to start using face recognition.

This tech blog discusses in detail the main points that emerged in the first study day about the legal and ethical aspects of facial recognition. We also look at the main legal and ethical aspects in the Uitgepakt (link in Dutch) section of META (META 2022/4 and META 2022/5), and the ethical questions are discussed further in an article in faro | tijdschrift voor cultureel erfgoed ('cultural heritage magazine' 15 (2022/2) (link in Dutch).

Among other things, the ethical challenges relate to compiling reference sets, potential algorithm biases, possible job losses caused by automation, working conditions for data labellers and the impact on the environment. The legal challenges relate to copyright protection, portrait rights and personal data protection.

2. Scaling up

Another challenge that emerged during the study days is how collection managers can write the metadata that this technology obtains to their collection or image management systems. The facial recognition results can only be used optimally when they’re written to these systems in a useful way. One question that comes up straight away is whether current management systems are actually ready for this. And the answer partly depends on what we want to write, exactly. It could be anything from a text string with someone’s name, to a person uniquely identified by an internal or external identifier (with a score indicating how likely it is that they are in fact the person depicted), the exact position of the person in the photo, or the video time code when the person appears.

A related question is whether this should be written in the collection management system (CMS) or digital asset management (DAM) platform. And how does the metadata from the facial recognition technology need to be structured for institutions that manage collections to import it as efficiently as possible? One aspect of this question is which file format to use; the FAME partners most commonly use JSON, XML and CSV as workable file formats for importing data into their management systems.

But when institutions that manage collections want to include metadata that has been generated (semi-)automatically, they need to decide whether they should treat this metadata differently from metadata created manually. Possible ways for dealing with this include:

The choices that collection management institutions make for this are closely related to what you want to present to your end user. How much uncertainty/noise do you allow and how do you display it? What’s the best balance between offering enriched metadata versus the risk of false positive matches? Manual validation requires additional work and isn’t always faultless, so organisations that want to go down this road will need to work out who’s going to do it. Will this be a (new) task for collection employees? Do you work with a limited number of properly supervised volunteers or go straight for crowdsourcing? The answer partly depends on how you can develop your facial recognition project, which is limited in time, scope and resources, into a sustainable and structured task with clear roles and responsibilities for the employees involved.

Another reason for including as much metadata as possible is to be able to reproduce certain processes in the future. Technology is constantly evolving and there may well be optimised workflows that produce (even) better results within a few years. The ideal reference set might also (need to) change sometimes, for example because there are new and better photos available, or because people get older and it’s best to reflect the age variance in the reference set. It might then become useful to check whether better metadata can be created for photos for which the current metadata status is uncertain.

3. Impact on collection registration

The study days also looked at how to compile and share reference sets. Good reference sets are a crucial aspect in the workflow, but creating them is a very time-consuming task. Two factors determine the extent to which this work can be partly automated: the availability of open data (including photos) on the web, and the amount of data that collection management institutions have about people in their collection that is linked with external authorities. Open data that is accessible via an API can be requested in bulk, and the links with external name authorities ensure people can be uniquely identified without manual checking or research. They’re also often the main anchor point for retrieving linked pictures (e.g. Wikidata).

Scaling up facial recognition would be simplified if organisations could share compiled reference sets with each other because the same people can potentially appear in different collections. An efficient method would mean that we could avoid multiple organisations partially reproducing the same work. But there are a number of legal, ethical and technical hurdles to overcome to make this possible. There is little problem sharing a vector profile of someone’s face in terms of copyright as there is no copyright involved. But sharing photos that make up part of the reference sets is potentially more problematic because they may be subject to copyright and/or portrait rights. Exchanging data is also risky in terms of personal data protection, of course. Given the fact that the workflows and software used in different facial recognition projects aren’t completely identically and are furthermore subject to change over time, vector profiles are neither stable nor interoperable between different workflows. As soon as a certain parameter changes, so does the vector profile.

But as a sector, we can work on better name authorities. An initial way to do this is to expand existing name authorities with collection management institutions’ available data. In the FAME project, we’re mainly working with Wikidata. The richer the data for people relevant for Flemish collections in Wikidata, the easier these people can be unambiguously identified. Another method could be to develop a specific Belgian or Flemish name authority. ODIS comes closest in this respect, but currently has neither the status nor the ambition to be the name authority for Flanders.

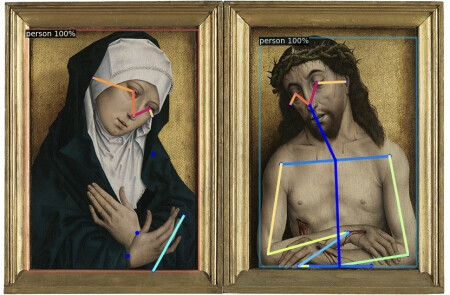

Image: facial detection applied to ‘Mater Dolorosa en Man van Smarten’, Anonymous Master, Musea Brugge, photograph by Hugo Maertens, public domain

4. Technical infrastructure

Not all heritage organisations have the knowledge and resources they need to implement their own facial recognition systems. So how can we work together as a sector to share the technical infrastructure and associated expertise required? If we can define what technical infrastructure is necessary, and what it needs to be able to do, in theory we can centralise it in such a way that different organisations can make use of it. This would also partially remove the need for specific expertise in every collection management organisation. But sharing technical infrastructure implies a scaling up, which has a big impact on the relative price. And technological components for facial recognition are evolving lightning-fast. So it’s possible that the scale of the Flemish cultural heritage sector and the support it can offer is not sufficient to manage and maintain such a centralised infrastructure.

Physically sharing infrastructure isn’t the only option, however; it’s also possible to provide centralised facial recognition as software as a service, which collection management organisations can simply pay to use. Purchasing existing services from (often large international) companies is not mutually exclusive from developing our own Flemish services.

Existing products have the advantage of being ready to use and good quality, but the disadvantage that they often don’t have transparent algorithms. In-house development allows for optimal alignment with particular requirements and a focus on specific workflows, but that takes time. And there is then no budget for buying software because it is being used to pay for people’s time instead, which allows for certain principled choices, e.g. for open source and ethical values. Crucial considerations for both options include the desired level of control on one hand, and the usability of off-the-shelf solutions (both in terms of quality and scale) on the other.

Programme overview of the three study days

The legal and ethical challenges were the subject of the first (online) study day on 18 January 2022. On the programme:

A brief introduction to the topic from a broad social perspective by Dominique Deckmyn (Culture and Media editor, De Standaard).

Explanation of the legal framework by Joris Deene (lawyer, Everest Law).

Keynote speech by Catherine Jasserand-Breeman (post-doctoral researcher, KU Leuven Centre for IT & IP Law).

Online poll with ethical questions for participants

Explanation of how the FAME project is dealing with legal and ethical aspects.

Panel discussion with specialists and experienced professionals, with Q&A session. Panel members: Steven Verstockt (ID Lab), Catherine Jasserand-Breeman, Tim Manders (Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision)

The second study day (again online) took place on 22 February 2022 and also consisted of a number of presentations with a panel discussion to conclude:

Presentations:

Introduction to the topic by Rony Vissers (meemoo)

Technical workflow within FAME and the challenges related to scaling up by Kenzo Milleville (IDLab)

Challenges and requirements for scaling up facial recognition systems in the Flemish cultural heritage sector by Rony Vissers (meemoo)

Future facial recognition plans at meemoo: the current status by Matthias Priem (meemoo)

Experiences and challenges with facial recognition technology at VRT by Jasper Degryse (VRT).

Panel discussion: rolling out facial recognition in day-to-day description processes. Panel members: Jasper Degryse (VRT), Henk Vanstappen (Datable), Phaedra Claeys (ADVN)

The third study day took place in person with project partner ADVN on 29 March 2022, and focussed on the impact on collection registrations. The second and third study days’ topics also overlapped somewhat. The scale at which collection management institutions use facial recognition to create metadata affects their ability to deal with this metadata to describe collections. On the programme:

Welcome by the ADVN directors and general introduction

Alec Van den broeck (former VKC) on the Saloncatalogi project

Nico Vriend (Noord-Hollands Archief) on the Krant en Foto (Newspaper and Photo) project

Roeland Ordelman (Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision, CLARIAH): machine-generated metadata at the Netherlands Institute for Sound & Vision and CLARIAH

Panel discussion: Behind the scenes in Flanders. Where are we? Brief explanations by:

Lennert Van de Velde (meemoo)

Joëlle Daems (FoMu)

Wim Lowet (VAi)

Diethard Vlaeminck (KOERS)

Phaedra Claeys (ADVN)

Tom Ruette (Kunstenpunt)