Facial recognition: what are the legal and ethical aspects?

- Tech Blog

Lots of collections currently have hardly any descriptive metadata, which limits the findability and searchability of their content and prevents them from being reused. Adding metadata manually is also very time-consuming task, which is why we’ve set up two projects to investigate what possibilities artificial intelligence can offer for automatic metadata creation. This technology needs to be treated with caution, however. In this tech blog, we take a close look at the legal and ethical challenges.

The two projects in brief

Legal versus ethical

We need to pay close attention to the legal and ethical contexts when using a technology such as facial recognition to add metadata to cultural heritage. This technology is not neutral or innocent, after all. It can serve noble aims within a correct legal and ethical framework, but it can also restrict or threaten the rights and freedoms of citizens in other contexts – just consider nuclear energy or the use of drones, for example, as well as artificial intelligence.

So what do we mean by ‘legal’ and ‘ethical’, exactly? Well, legal covers everything related to the law, and ethics are the moral principles that guide our behaviour and actions. Legislation is often based on moral or ethical principles, but ethics goes much further than just what is included in legal texts. When using face recognition, we therefore make ethical considerations as well as building in the necessary legal safeguards.

Legal issues

We need to tread very carefully when working with technologies such as face recognition, and we also have a legal obligation to process the personal data for the people portrayed in a responsible way. We’re taking this into account in the FAME project, including by making sure we heed specialist legal advice. We also need to take specific legal guidance into account in the GIVE metadata project, so we don’t lose sight of privacy issues and can be certain we have a proper legal framework.

FAME: copyright, image rights and GPDR

1. Copyright

It was important to keep three legal aspects in mind for the FAME project. Firstly, we’re working with photos that are protected by copyright, which means that we can only use photographic content within the legally defined exceptions or with the rightsholders’ permission. The aim of the project is not to publish copyrighted content, but to use reference materials to train and improve algorithms, and add metadata to the defined sets of photos. We can invoke the education and research exception for this.

We can invoke this exception because the main aim of FAME is to develop best practices for identifying people in photos and videos using (semi-)automated face recognition, and we’re investigating how we can use metadata to improve face recognition accuracy. We’re doing this in close collaboration with an accredited research institute, our technical partner IDLab from Ghent University.

2. Image rights

‘Natural persons’ in Belgium also have image rights, of course, which means they need to give their permission for their image and likeness to be made and used, including for all reproductions and publications of these photo(s). This permission is presumed for public figures on the condition that the images are created while they’re exercising their public activity, and this exception is hugely important in the FAME project. We therefore chose our datasets with this in mind, but we still need to make sure that all the people portrayed (such as one-off actors, spectators at cycle races, public figures in a non-public setting…) are indeed taking part in a public activity.

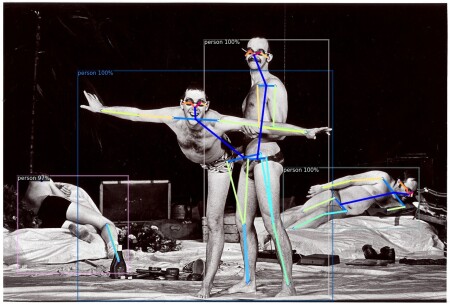

Image: Dirk Pauwels and Josse De Pauw in ‘Ik wist niet dat Engeland zo mooi was’ from theatre company Radeis, image by Michiel Hendryckx, CC BY-SA 4.0

3. GDPR

Finally, we need to take the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) into account. The GDPR considers the creation, saving and use of photos on which people are portrayed to be (personal) data processing, which means it is strictly regulated. The processing of this ‘biometric’ data with a view to identification is prohibited in principle unless you can invoke an exception. And as a statutory body, meemoo is authorised to invoke the following ground for processing: ‘processing is necessary for the performance of a task carried out in the public interest or in the exercise of official authority vested in the controller.’ (GDPR Art. 6.1.e).

Meemoo can also invoke a more flexible regulation provided for in the GDPR, specifically for processing with a view to archiving in the public interest for scientific or historical research or statistical purposes (GDPR Art. 89.1-3). The regulation does however state that it’s important to maintain the right balance for the privacy and rights of those involved, and that the necessary technical and organisational safeguards must be in place.

GIVE: legal framework

We took a significant step forward in the preliminary phase of the GIVE metadata project by carrying out a DPIA (Data Protection Impact Assessment) to satisfy the regulation with regard to personal data protection. We explain what this means in detail and how we went about it below.

1. Outlining the context

One of the main themes in the GDPR is ‘accountability’. The GDPR makes organisations responsible for demonstrating compliance with privacy rules, which means that as a data controller, organisations need to analyse and assess the risks of a particular processing, and limit these risks as much as possible to ensure the protection of the rights and freedoms of those involved and their personal data remain safeguarded.

For any planned processing operations that are likely to risk the rights and freedoms of natural persons, and in particular where new technologies are used, controllers need to assess the impact of their intended processing activities on personal data protection even before processing. This assessment is called a Data Protection Impact Assessment in the GDPR, but this is a bit of mouthful, so it is generally abbreviated simply to ‘DPIA’.

Image: Minister Nijpelshands over big key to President of the Chamber Dolman, image by Rob Croes, Anefo, CC0

2. How did it go?

Meemoo carried out a DPIA in the preliminary phase of the GIVE metadata project in close consultation with the Data Protection Officer (DPO). We started by drawing up a general description of the intended processing to create an overview of the types of personal data that we’re planning to process, the purpose of the processing, the source of the personal data to be processed, the people involved, etc.

This overview enabled us to proceed to a second analysis in which we could identify the possible risk for every processing activity. We also considered the type of damage that each risk could incur, and the probability and severity of its impact. These variables served as the basis for the total risk which we arranged in a risk matrix. We then provided our meemoo colleagues in different teams and from different backgrounds with input about the measures that we could take to minimise this total risk as much as possible, and produced organisational, technical and legal measures for each processing activity.

One example of these processing activities is the sending of a limited dataset to various potential suppliers who can use machine learning to add metadata to heritage collections. This means they can furnish our test set with metadata and we can use the results to evaluate the techniques used.

Keeping the volume of the test set small, and compiling it in such a way that it doesn’t include any content with sensitive personal data, limits the risk for this processing activity. We use encrypted transmission (sFTP, HTTPs) to encrypt the data we send to them, and our up-to-date servers and services further reduce any technical risk. We’ve also made detailed provisions for personal data processing and incorporated them in the specifications which will form (part of) the processing agreement. This includes the condition that candidate suppliers delete all files after processing. Finally, we will sign NDAs with all the processors involved.

Conducting all our activities in this way ensures only a few risks remain. We discussed and described these remaining risks, but after weighing them up we decided they were so small that they were acceptable.

3. Conclusion?

This procedure allowed us to assess both the risks and how they will be managed in the preliminary phase of the GIVE metadata project. We will effectively implement the organisational, technical and legal measures that we’ve devised as the project progresses, and the DPIA will serve as our framework and guiding principle.

Ethical issues

Alongside legal correctness, it’s important to ensure that we apply artificial intelligence in an ethically responsible way in the cultural heritage sector. And because the facial recognition part of the GIVE metadata project is still in its infancy, in this tech blog we look in more detail at some of the challenges encountered in the FAME project. We will of course take into account the concerns and points for attention that arose in FAME.

Hoe do we put reference sets together?

Good reference sets are essential for facial recognition technology. These are collections of photos that we are certain portray a particular person. An algorithm compares these reference photos with photos from the target collections, and calculates the probability of the people portrayed appearing in them. But how ethical is this mass collection and storage of photos from the internet without permission from the people portrayed? And is it responsible to share these sets outside of current projects?

Image: Cyclist Piet de Wit married, image by Bert Verhoeff, collectie Anefo, CC0

How do we deal with this?

We only use public figures in the creation of reference sets, which reduces the number of legal and ethical barriers, and limits any impact on private individuals. When using open content for AI, our view is that we need to look at both the ultimate goal (what we’re doing with the photos) and the possible negative consequences for the people portrayed to determine whether it’s ethically responsible to collect photos en masse for face recognition purposes.

We also need to ask ourselves whether we can share these reference sets outside the project. There is certainly a potential gain in efficiency within the Flemish cultural heritage context from sharing and reusing reference sets. For example, it allows institutions to streamline the time- and labour-intensive process of compiling reference sets. But the sharing of photos also implies a loss of control, and exactly how we maintain this balance remains an issue. Even though we’re seeing a global trend towards regulating the use of AI, it’s still essential to maintain professional ethics alongside these regulatory frameworks. The societal mission and value framework provided by cultural heritage organisations can help to shape these professional ethics.

Bias in algorithms

A further challenge involved in the use of AI applications is that algorithms can lead to bias. Racial and gender biases can be particularly prevalent within facial recognition applications, and there’s a risk they could reinforce or increase existing social inequalities, so it’s important to avoid bias wherever possible. If this isn’t completely possible, we need to limit any consequences and provide visibility for the potential biases as much as possible.

How do we deal with this?

We’re helping to avoid biases in FAME through the use of carefully created reference datasets in each pilot project, but this still isn’t comprehensive. Bias can even occur already in the stage when the software is detecting people in photographs. Distinguishing a ‘person’ from a ‘non-person’ on photos requires a certain standardisation, and this is necessary to create useful categories and avoid false positives and negatives. The characterisation of the ‘person’ concept doesn’t just determine whether too many ‘non-persons’ are categorised as ‘persons’, but also whether all people are recognised equally well, regardless of their physical features or clothes, for example.

In the FAME project, we used a sample to manually check the algorithm used for bias, and the results from this sample are reassuring at first sight. Hats, sunglasses, headphones and even face masks, for example, did not appear to be a problem for automatic face detection.

Automation as a threat to jobs

One common criticism of new technologies, and artificial intelligence in particular, is that they pose a threat to jobs done by humans. This fear might be humane and understandable, but it’s not really well-founded. Research has shown that even though technological evolutions may well lead to certain jobs disappearing, they also result in the creation of new ones. It is true, however, that increased automation can cause the type of work that needs doing to change. Low-skilled jobs are the most vulnerable here because they often involve repetitive tasks.

Image: Women in industry, tool production, 1942, Ann Rosener, public domain

How do we deal with this?

Within FAME, we’re focusing on automating tasks that aren’t currently being undertaken because of a lack of time or personnel – so machines will not be replacing any people. People can think and reason, whereas machines are programmed to make calculations. Cooperation between person and algorithm remains crucial, however, and the role of the human behind the machine even becomes more important in a certain sense.

Working conditions for data labellers

Training algorithms with large amounts of data requires a lot of work. And the people who perform this data labelling work can vary, as can the circumstances under which it is carried out. Sometimes it involves properly paid permanent employees, and sometimes it’s done by trainees or volunteers. Others rely on crowdsourcing, ghost workers or click workers in low-wage countries with poor working conditions. Within FAME, we’re using software that has already been developed only for the face detection part. We know who developed the Insightface model that we’re using, but not what purpose it was developed for or under what conditions. The way in which cultural heritage organisations tackle the manual validation of matching results also remains an ethical concern.

Impact on the environment

Face detection and recognition are processes that require a lot of computing power and energy. This, and the software development that preceded it, both demand lots of energy-consuming training. Unfortunately, a substantial proportion of this energy does not come from renewable sources. As with all the ethical issues raised above, both the reduction of adverse effects (e.g. through more energy-efficient workflows and algorithms) and transparency are important points for attention.

What do we learn from these five ethical issues? The Montreal AI Ethics Institute adopts Saint Ambrose of Milan’s four cardinal virtues as a surprisingly suitable guide for ethical AI applications:

Prudentia - caution, sensibility, wisdom

Justitia - righteousness, honesty

Fortitudo - valour, perseverance

Temperantia - moderation, discipline

Preventing undesirable outcomes of course remains necessary, but the best way to guarantee an ethical approach to artificial intelligence may well be to ensure that everyone involved in an AI project adopts these four virtues as their guiding principles. This puts the focus on people’s behaviour, which goes further than just the legal framework. Furthermore – as history has already proven – these virtues possess a timelessness that can endure rapidly evolving technologies.