Digitisation versus digital migration

- Tech Blog

At first glance, there is a strict distinction between carriers of analogue and digital audiovisual information. In practice, however, this distinction is not always clear. The word ‘digitisation’ doesn’t always cover the load and is therefore not always used correctly. In this tech blog, we will clarify the terminology by diving into history.

According to the definition, digitisation means to convert analogue into digital information. At meemoo, we don't think this strict approach is enough. We not only strive to make audiovisual information digital, we also want to secure this digital signal in the form of a file. By doing so, we can store the files to be placed in our mass storage infrastructure, which uses servers and tapes. This allows us to manage the files and their content much faster and more easily: move, copy, check, analyse, describe, and more.

There are all kinds of audiovisual media out there: from records and cassettes to video tapes and films. For the vast majority, digitisation is the most important step, and, simultaneously, it’s also the one that attracts the most attention. That is why we very often use the term ‘digitisation’ as a pars pro toto for the much wider range of activities that go with it, even if, strictly speaking, it’s not always correct.

From analogue to digital

When talking about audiovisual material, we usually refer to carriers of analogue versus carriers of digital audiovisual information. In order to clarify the distinction between the two, let's take a look at the history of audiovisual preservation. Over the past two centuries, the ways in which we have stored this material have evolved at a rapid pace. This led to the creation of a whole group of carriers in the midst of the transition from the analogue to the digital world.

The evolution of analogue to digital preservation in a nutshell

Digital information essentially comes down to nothing more than information expressed in numbers. Each number is coded in a combination of zeros and ones. Nothing new under the sun: mankind has been storing information in this way for centuries.

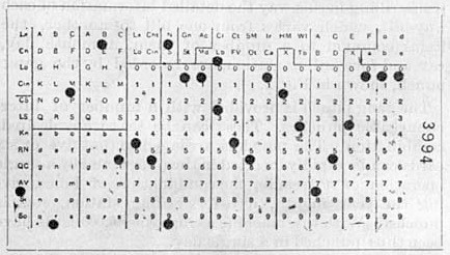

As early as the 19th century, digital information was converted into sound, albeit in a very simple way. Cardboard books for street organs used the same principles as punch cards: depending on the presence or absence of a hole in the cardboard, air was forced or blocked through the organ pipes. This is how music was created. For decades, the digital preservation of audiovisual information went no further than that.

Simultaneously, the invention of various analogue carriers for audiovisual information, such as the phonogram and the gramophone record, made it easier to store complex signals, like speech, and (in the case of the gramophone) also replay these signals. These techniques were all based on an engraving with a needle. On the cusp of the 20th century, the steel wire recording was invented: the basis for all later magnetic tape-based information carriers. By applying metal to a wire and magnetizing the particles, it became possible to record sound. At this point,carriers for complex audiovisual information existed, and on top of that we had a digitally coded, audiovisual storage medium: the street organ cardboard books. We did not yet, however, have a combination of both.

In 1937, pulse code modulation, a way to digitally present analogue sound , was invented. In 1967, this way of digitally coding sound information was eventually combined with magnetisation on a tape. This way of working remained in use until the beginning of the 21st century, think for example of the Digital Betacam and Digital Audio Tape.

From digital signal to file

Pulse code modulation made it possible to raise the preservation of audiovisual material to a higher level. Yet its success proved limited, due to three major drawbacks.

Firstly, this method of encoding is extremely space-consuming: a huge amount of tape was needed to store even the smallest piece of moving image or sound.

Secondly, a tape isn’t considered very practical, because the information is stored in a linear way: you have to wind it to the place where the information you are looking for is stored. By the way, this also applies to LTO-tapes, a storage medium very popular in large audiovisual archives today - we use them at meemoo as well.

Thirdly, the digital signals are not stored as files. This means that the way digital information is structured differs from carrier to carrier. To read the information, you not only need the right playback equipment, but also knowledge about the structure and the code. For this we need to take a look at the history of file storage.

Saving files

The word ‘file’ has been used in the context of digital information since the 1950s. But the real design of digital information as files as we know it today only came into existence in the 1970s, in parallel with the first floppy disks. On these, for the first time ever, one could store any file format. The disadvantage? The capacity was barely 1MB!

Therefore, the storage of digital information, the storage of complex audiovisual information and the storage of files could only come together under the condition that either the audio and video were very small, or the storage media had sufficient capacity. Both movements occurred more or less at the same time. The oldest standardised digital file format for moving images, H120, dates back to 1984. The resolution was 176 by 144 pixels and it ran at 30 frames per second. Playing this required from the computer that it processed the images at 2MB per second, which was a huge accomplishment in those days!

But once that got off the ground, things went fast. The capacity of the storage media grew very quickly, and the capacity and computing power needed to play sharper, clearer and more beautifully coloured images also grew. Ways in which to code images in a nicer and also smaller way, was established in standards for file formats, which also had to evolve very quickly. Thislightning-fast evolution ensures that - even though the signal is digital and file-based - we can still have trouble recognizing, transferring, reading and playing files.

Digital migration

This account demonstrates that there are many carriers out there that do not simply contain analogue or digital audiovisual material. They contain audiovisual information that is already digital, but does not yet exist in the form of a file. Or it goes a step further, as with the DVD: the carriers contain audiovisual material - digital and in file form - but are not easy or quick to manage because they are not stored in an infrastructure for digital mass storage.

At meemoo, we want to save and store this information. Since the information is already digital, the term ‘digitisation’ is not sufficient. We prefer the terms ‘digital migration’ or ‘digital transfer’.

This blogpost was originally written by Brecht Declercq (former manager Digitalisation and Acquisition) for the website of Digital Preservation Coalition. We published it in a slightly modified form.